The Eight Hour Day movement

The Melbourne General Cemetery is a treasure store of Victoria’s history, and it was one of my favourite walks during lockdown.

In the November edition I wrote about Brettana Smyth, pioneer of women’s rights, who died in 1893. Later, I discovered her grave in the Melbourne General Cemetery. There was a plaque recording that it had been renovated by the CFMEU. On contacting the union, I found that the renovation had been sponsored by the now defunct Labour Graves Committee and unveiled by Joan Kirner on March 13, 1995.

I also learnt that the committee had sponsored the restoration of the graves of six men, all of whom were involved in the Victoria’s Eight Hour Day movement. Besides the three men I have written about here were George Booker, Johnston Ormiston and Freeman Manuel. I will write about Manuel for the next edition.

Conditions for working people in the early days of settlement could be gruellingly hard. A group of men, many of whom were immigrants from the United Kingdom with a history of agitation for reform, got together to lobby for improved conditions. Their plan was to confront employers with their initial demand for an eight-hour day – an equal balance of work, sleep and leisure.

The culmination of their planning took place on April 21, 1856, when a number of masons working in Melbourne downed tools and marched to Spring St where Parliament House was under construction and where the masons were agitating for better pay. There was much public sympathy for the reform and the workers finally won the day. It was up to each industry to negotiate their own hours and conditions, but the precedent had been set and the eight-hour day soon became an accepted norm as other industries took on the fight. The men who supported the movement were highly respected throughout their lives and many were venerated at the time of their deaths.

One very grand tombstone in the cemetery, not illustrated, is that of James Galloway. He was one of the founders of the eight-hour movement. He died in 1860 at the age of 32. A large, elaborate memorial was paid for by unionists in 1870. It was renovated and unveiled by the Prime Minister Gough Whitlam on March 9, 1992.

Thomas Topping was another important member of the movement. His tombstone records that he was one of the founding fathers of the Eight Hours Movement. When he died in 1895 the Melbourne Herald reported that, “The funeral promises to be a very large one, the Trades’ Hall Council, Eight Hours’ Association and kindred bodies having signified their intention of taking part”.

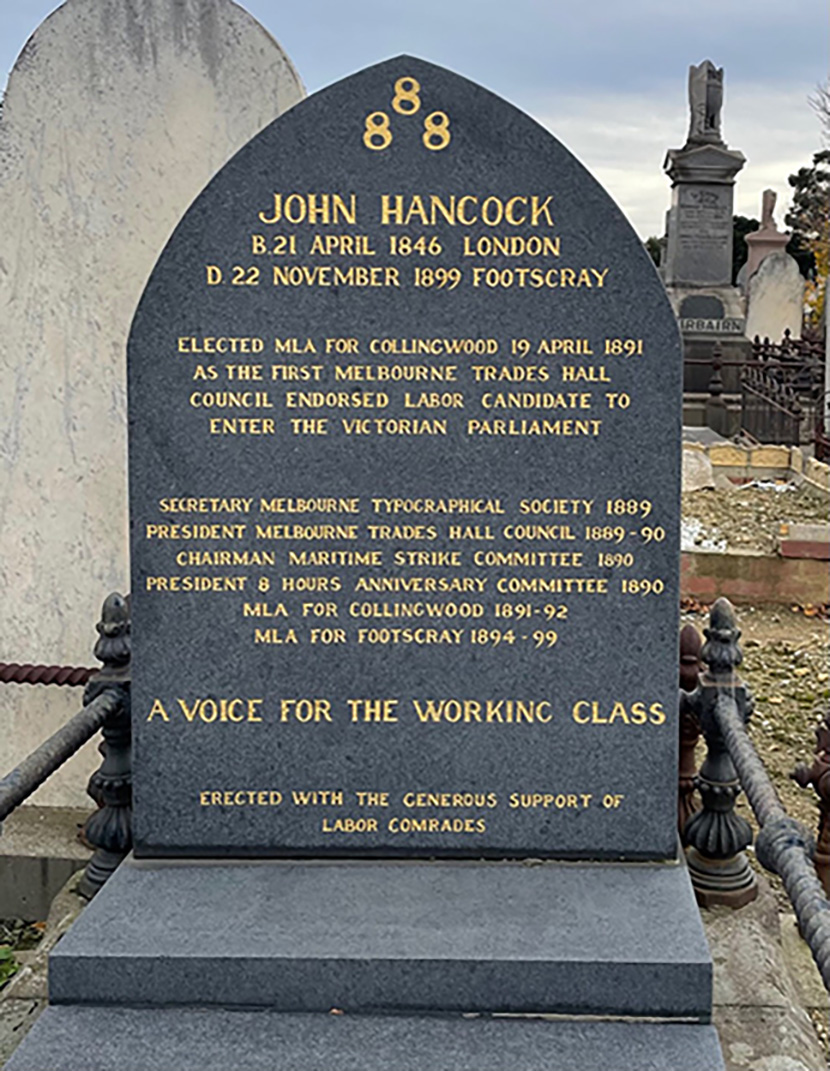

John Hancock (1846-1899) was born in London and migrated to Australia in 1884 where he was prominent in trades union issues and in leadership of the ongoing Eight Hour Movement. He was elected as a Labor candidate to the Victorian parliament in 1891, having been endorsed by the Trades Hall Council. His gravestone proclaims him “A voice for the working class”.

The fight for fair and equitable working rights continues, but it’s important to remember those whose vision and dedication began the process. A walk-through Melbourne General Cemetery can remind us of the lives of the men and women who preceded us. •

Jo Ryan unveils Ordered Chaos at Blender Studios

Download the Latest Edition

Download the Latest Edition